Empress Theodora is an icon (literally)

Life, culture, religion, and the powerful female ruler of the Byzantine Empire

Welcome back to another one of my art history rambles! This is a version of a project I worked on a few years back about Empress Theodora and Byzantine art. This is a long one, so be prepared…I hope you enjoy! (See the end of the piece for citations and references).

Introduction

The Empress Theodora ruled with her husband, Emperor Justinian I, from 527 to 565. Her origins are consistently debated by scholars and historians, and the her reign is seldom acknowledged in contemporaneity. However, she ruled, essentially, as an equal to her husband and quickly became one of the most powerful women in Byzantine history.

Recorded history of Byzantium during this time was largely written by prolific historian, Procopius, who was known for creating dramatic narratives surrounding historical events. Thus, several of his works have little basis in fact, yet they are still referenced as an accurate account of the Byzantine world, particularly surrounding Theodora’s life and reign. Current scholarship has begun to uncover details about her life that were overshadowed by Procopius’s negative portrayal of powerful women. Through a careful analysis of architecture and art created during the era of her reign, one can begin to understand the truth behind Theodora’s history and, further, the historical context and cultural influences of her reign.

Empress Theodora

Empress Theodora was a polarizing figure in the Byzantine world, her past shrouded with ambiguity. Procopius crafted his masterwork, Historia Arcana, or Secret History, as a commentary on relationships and politics within the imperial and governmental sphere. Historia Arcana, now viewed as borderline blasphemous by some scholars, provides a view of Theodora’s life and origins that may not be found elsewhere. According to Procopius, Theodora was raised somewhere in the Middle East – Syria, Alexandria, or Cyprus – and was employed as a dancer and sex worker, although her true origins are unclear. Born to a bear keeper, “Theodora was a product of the Hippodrome and the stage” (Foss 2002, 141). Procopius claims that she increased her social status through her profession and eventually met Justinian I who fell madly in love with her, making her his consort. Procopius describes her as vindictive, vengeful, and spiteful towards other members of her court, particularly other women (141).

However, Procopius’s Historia Arcana does contain morsels of truth, as uncovered by other Byzantine scholars. Procopius explicitly describes Theodora as a “harlot queen,” claiming that “she had many lovers and many abortions” (Foss 2002, 150). While “harlot” certainly is not an appropriate word to describe the future empress, there is some truth in Procopius’s assertions. Theodora worked alongside her sister, Comito, as a dancer and mime, later becoming a well-known hetaira, or a performer and courtesan. Evans’s research reveals that Theodora and her sister were known to perform strip-teases which corresponded with popular stories of the time (Evans 2011, 33).

“Good striptease artists tease as much as they strip, and Theodora, it seems, knew her trade well.” (Evans 2011, 33).

The theatre was no place for “respectable women” and performers were often referred to as the “scum of society” (32). They commonly lived at the margins of society. Thus, Theodora would have been raised in relative poverty, likely forced into her profession due to lack of opportunities for low-income Byzantine women. According to Procopius, Theodora’s performances were a source of notoriety, and she found that people would either stare and leer at her or would turn away in scorn. Syriac historian, John of Ephesus, referred to Theodora as “Theodora from the brothel” in his writings, further emphasizing the low opinion of “respectable” Byzantine citizens towards theatre performers (7).

To Procopius’s merit, some of his assertions about Theodora’s sexuality may be true. Some texts show that Theodora gave birth to a daughter after several abortion attempts failed. Her daughter was certainly not Justinian’s since Theodora gave birth around the age of 15 – long before she met the emperor. However, little detail of her daughter remains (35). Theodora and Justinian’s marriage remained completely childless, which could likely be attributed to Theodora’s history of abortive attempts while working as a performer and former courtesan.

However, without the background provided by Procopius in Historia Arcana, Theodora’s history looks quite different. Fisher and Foss both note that Theodora was a pious woman who prioritized her faith over anything else. Foss cites contemporary texts and research surrounding her early life, which is somewhat obscured without Procopius’s sordid details. Some contemporary scholars argue that Theodora was the daughter of a devout Monophysite father and was raised in a faith-filled household which later influenced her religious sympathies as Empress. She was only permitted by her family to marry Justinian provided that she maintained her Monophysite faith (Foss 2002, 142). As a result of her devotion to her faith, Theodora became an outspoken advocate for religious freedom and protected Monophysites from persecution during her reign. She was known within the Coptic and Syriac Churches as “the believing queen” and the co-founder of both churches, where reverence towards her continues in the contemporary era (Evans 2011, 7).

Monophysitism, initially defined in the Council of Chalcedon in 451, was the belief that Christ was not equally divine and human. Instead, he had divinity with no regard to his humanity. This idea was challenged during the 4th through 6th centuries, and as the Church further debating the nature of Christ, Monophysitist beliefs fell into obscurity, facing discrimination from Church authorities. The Council of Chalcedon spurred this discrimination, asserting that Christ had both human and divine natures. Thus, Theodora’s devout Monophysite faith was challenged by Church authorities and was called into question throughout her life. Monophysitism was declared heresy by Chalcedon, although this was disputed in the Orthodox church after the schism between Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Despite the persecution her subjects faced for their faith, Theodora was allowed to continue practicing Monophysitism, even after her ascension to the throne in 527 (Foss 2002, 143).

Theodora protected Monophysite laypeople and clergy alike from persecution, hiding them in her palace and providing food, water, shelter, and clothing for them after they fled their homes out of fear of Church authorities (143). She hid a powerful bishop in her home for about 10 years until it was safe for him to reenter society after the onset of systemic religious persecution in the 530s that was introduced by Justinian. The pope attempted to excommunicate Theodora for her beliefs and in retaliation, Theodora and one of the members of her court, Antonina, the wife of general Belisarius, attempted to install a new pope to prevent further persecution of her people. Theodora was known as, Foss aptly states, the “protector of her church” (143).

Procopius seldom mentions Theodora’s pious nature and neglects to describe her faith in any detail. Instead, he reduces her, simply, to Justinian’s wife and consort, emphasizing her penchant for vengeance and vindication. The term consort that Procopius suggests minimizes Theodora’s identity and breadth of power within Justinian’s court, since she held significant influence over her husband for the entirety of her reign. Contemporary Byzantine scholars have noted that Procopius’s Historia Arcana was likely based on gossip and his own preconceived notions about women in the empire. While his work was intended to discredit Justinian and his court, Procopius consistently sought to minimize Theodora’s role in Byzantine history by demonizing her. According to Fisher, Procopius’s prejudice against women is clear in his work as he “apparently hated domineering women,” subsequently attacking Theodora and members of her court, especially Antonina (Fisher 1978, 253-279).

When compared to contemporary scholarship surrounding Theodora’s history, Procopius’s Historia Arcana must not be taken as an accurate account. Rather, Historia Arcana can be reduced to a combination of fact and fiction, only loosely based in truth. The same can be said of Antonina; Procopius reduces her power by describing her similarly to Theodora – vengeful and vindictive – while ignoring her influence on her husband Belisarius. In some ways, writes Fisher, “Antonina reflects and extends the characterization of Theodora,” further proving Procopius’s prejudice toward independent women (Fisher 1978, 267).

The Nika Rebellion

The Nika Rebellion was a violent series of riots and battles between warring factions which led to instability and fear within the imperial family and Byzantine leadership. Two separate factions of chariot performers from the Hippodrome, known as the Blues and the Greens, were each supported by different government leaders. The factions essentially worked as unions, both in the arena and out, and the government could not function without their support, as each faction held a specific stance on political, religious, and social issues. Justinian and Theodora both supported the Blue faction, and Theodora’s partiality in particular likely stemmed from her life in the theatre and her experiences as a worker in the Hippodrome as a young woman. According to Evans’s account, Theodora and her sisters were jeered during one of their first performances, and the Blues were kind enough to take them in since there was a vacancy for new performers. Evans states that “The Blues had rescued [Theodora’s] family from penury and the family reciprocated by transferring its loyalty to them” (7).

Tensions between imperial leaders and the Blue and Green factions came to a head in 532 following widespread corruption of leaders along with a failing and waning war against the Persians (Greatrex 1997, 62). The city was burned by the Blues and Greens, who then fought on a united front. The united factions, referred to as the Nika, sought to install Hypatius as the emperor. The factions held an improvised ceremony for Hypatius, calling him Augustus and adorning him with imperial regalia (77). Once this occurred, Justinian moved to seal off the palace to protect himself, attempting to take the path of least risk. However, Theodora stood firm. She believed that Justinian should take an offensive stance against the riots to protect himself and current imperial leadership from the people seeking to remove them from power. The violence peaked within five days of the start of the riot, right as Hypatius was installed as interim emperor. While senate members pressed for a conservative, low-risk approach to the riots, Theodora ensured that Justinian’s court and the imperial leadership remain assertive in their efforts. Procopius quotes her in his History of the Wars: “‘No other policy seems best for those whose fortunes have come into the greatest peril than to act vigorously in the best possible way’” (Evans 1984, 380). Theodora continued to cite ancient leadership and political ideology to support her point. As Evans states, Theodora asserted that, “Royalty...was a fine burial shroud; the aphorism, which seems to have been famous enough, had it that “tyranny,” not “royalty” was the shroud” (380).

Her words emboldened Justinian’s followers and influenced them to continue to fight for him and imperial leadership. While it is unclear if Procopius’s quotations from Theodora’s speech are completely accurate, Theodora was still amain influence in spurring Justinian’s troops to continue fighting to end the rebellion. Procopius’s recollection of her speech certainly alters the reader’s understanding of her role in curbing the conflict. Without her powerful words and passion, it is likely that Justinian would have been removed from power, and that he and Theodora along with the rest of their governing body would be executed. Not only did Theodora end a riot purely through powerful words, she also saved the lives of important imperial officials with the goal of maintaining the stability of the empire.

It is conflicting to learn that Theodora crushed a rebellion that may have benefitted the Nika, as the performers and laborers in this faction were not entirely represented in government. Her words largely speak to her power over the political sphere in Byzantium at the time, rather than her compassion for her people. Nonetheless, she was simultaneously seen as an equal to her husband, evidenced through the architecture and art within churches constructed throughout her reign.

Hagia Sophia—The Church of Holy Wisdom

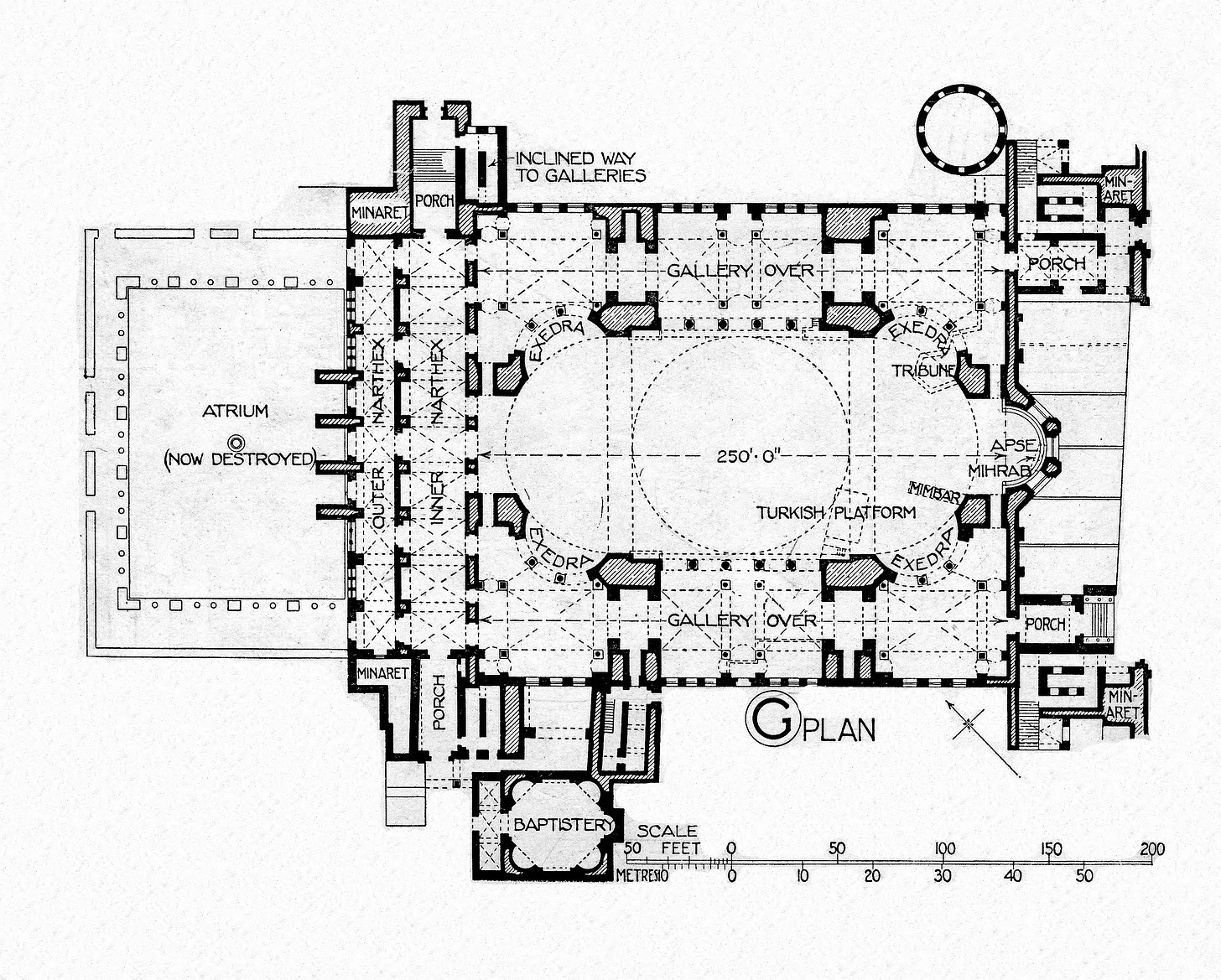

While the original foundation of the church dates to c. 4th century CE, Hagia Sophia did not see significant modernization and construction until the reign of Justinian I. The original cathedral was destroyed two separate times – once in the mid-5th century in a fire and a second time in 532 as a result of the Nika Riots. After its destruction, Theodora and Justinian became its patrons, funding its renovation. The church was reconstructed a second time after a major earthquake caused the main dome to collapse in 558, after which extra supports were added both inside and out to protect the church from further natural disasters (Murray 2003). The interior floor plan consists of a narthex running perpendicular to two upper galleries, one large dome surrounded by two smaller semi-domes, a central nave, and a small apse at the far end of the building, later converted to a mihrab following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. Minarets were added on the exterior along with the mihrab when Hagia Sophia was converted to a mosque under Ottoman rule.

Images of Seraphim, or three-winged angels and heavenly guardians, flank the pendentives of the main dome. These figures, while somewhat terrifying, draw the eye upwards, creating leading lines that meet at the center of the church’s main dome. While the center of the dome now contains Arabic script and verses from the Qur’an, it is likely that original mosaics from the 6th century were covered in plaster following the Ottoman invasion. Current scholarship has revealed that there may be a monumental mosaic of Christ hidden underneath layers of plaster in the dome, but there is no way to respectfully remove the plaster and Qur’anic script to uncover it due to the building’s history as both a church and a mosque, as well as concerns over the structural integrity of the dome itself (Hagia Sophia: Istanbul’s Ancient Mystery).

The Hagia Sophia was not just known for its beauty and splendor. It was also an important site for both Justinian and Theodora, providing a monumental backdrop for their reign. The Hagia Sophia was the site for Theodora’s coronation ceremony just three days after Easter Sunday. At this time, the oath of office was administered, and both Theodora and Justinian would have been confirmed as Augustus and Augusta of Byzantium (Evans 2011, 54). However, this coronation would have occurred prior to the drastic renovation of the church, when it was still a Basilica and not the massive sacred site it became after construction in the 530s. Theodora and Justinian authorized the reconstruction jointly, evidenced by the placement of Theodora’s monogram on the capitals of the church directly alongside Justinian’s (54).

Despite Theodora’s power and influence in the Byzantine world, she was still relegated to a lower status due to her gender. Since she was a woman, she was forbidden from sitting with her husband at religious services within Hagia Sophia. Theodora was no exception to the gendered rule, and she and her court were expected and forced, to sit in the church’s gallery or on the floor separate from men. However, despite the poor institutional treatment imposed on Byzantine women of all social strata, Theodora remained a generous donor and patron of Hagia Sophia. Her and Justinian contributed significant funding to maintain the church, so much so that it had a well-paid fixed staff, with 60 priests, 100 deacons, 40 deaconesses, 100 doorkeepers, 25 singers, and 110 readers (16). The Emperor and Empress ensured that bishops maintained a steady salary that rivaled that of military and government officials and exempted most clergy members from military service depending on their rank (16). Hagia Sophia was, in essence, a manifestation of Justinian and Theodora’s power over all aspects of the Byzantine world, proclaiming that even Christendom was under their control.

Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

The Basilica of San Vitale was also built during the reign of Justinian I and Theodora. The mosaics found on the interior walls, apses, and ceiling are arguably some of the most iconic from the Byzantine Empire, and many of the images of Christ, saints, and other holy figures are some of the only ones left in early Byzantine churches before the 8th and 9th centuries. This is likely due to widespread iconoclasms sponsored by their respective contemporary emperors and broader leadership.

Ravenna, Italy was restored to Byzantine control in 540 following a long occupation by the Goths. While construction on the Basilica had begun before the empire took full control of the region, it was not completed until after the expulsion of the Gothic king. To emphasize their new control over the area, Justinian I and Theodora had mosaics created in two of the Basilica’s apses.

Historian Judith Herrin describes the octagonal plan of the Basilica “unusual,” as it does not share many of the typical characteristics of Byzantine churches built during that era (Herrin 2020, 161). It is likely that the floor plan was inspired by Middle Eastern architectural styles which spread throughout the Mediterranean during this period (163). The ceiling above the altar is decorated with elaborate mosaic images, from floral and vegetal designs to religious imagery. The mosaic artists worked quickly and efficiently, ensuring that the plaster underneath was at the perfect consistency to accurately place polychrome and gold tesserae to create stunning religious scenes, including stories from the Hebrew Bible, the Twelve Apostles, and various male saints flanked by animals and vegetation (166).

“The church of S. Vitale was not completed for some twenty years. By that time, Ravenna was in Byzantine hands; the church was finished under imperial patronage and decorated with mosaics of Justinian and Theodora, as a symbol in reconquered Italy of the magnificence of the empire” (Browning 1987, 74).

The San Vitale Mosaics

Theodora

Theodora is shown wearing a deep purple chlamys – a type of robe or cloak that would rest on a dress or tunic – atop an embroidered gown, or gunna. Theodora’s gunna is embroidered with a scene of the three Magi from the Christian Bible woven in golden thread (Munroe 2012). She is covered in jewelry on her head and shoulders, including a maniakis collar and a crown, or a stemma, which was attached to hanging strands of mother-of-pearl and precious stones called a prependoulia (Munroe 2012). As the empress, Theodora would have had the most elaborate outfits out of her court, although they were similarly dressed in hand-woven fabrics and brightly colored silks. Munroe notes that the silks may have been of Sassanian manufacture, mirroring woven tapestries from the same era found in Egypt. Theodora holds a jeweled chalice in the mosaic, moving her hands to her side as if giving a gift.

The mosaic rests in an apse in the Basilica of San Vitale, and the church was created through generous donations and patronage by Justinian I and Theodora. Thus, the chalice may be representative of the basilica itself, as Theodora seems to hand it to an attendant at her side who willingly accepts it. Her transfer of the chalice mirrors the gifts of the Three Magi woven on her robe – the shading and tone of the chalice is similar to that of the golden thread used to weave the images of the Magi, and her gift of the jeweled chalice evokes the gifts of the Magi to Christ during the story of the Epiphany as described in the Book of Matthew. Theodora’s crown is surrounded by a golden halo, emphasized by a burgundy outline, further pointing to her close relationship with the divine.

Theodora is standing directly underneath a turquoise apse, mirroring those found in San Vitale. Her retinue is flanked by rectangular columns in a traditional Corinthian style. The columns are also jeweled with gold, white, and green tesserae, reflecting the design of the chalice and the jewels on Theodora’s stemma. A fountain sits atop another fluted Corinthian column, with stark white tesserae and elaborate shading to make the texture seem almost like marble. It may be a representation of a baptismal font, further reflecting the architecture of the basilica within the mosaic. A male attendant at Theodora’s side pulls back an ornately woven curtain, perhaps inviting her to walk through an entrance. The court seems to be moving towards the doorway since the body language of each member motions towards the left side - the women’s faces in profile are oriented towards the doorway and each woman’s robes flow towards the right side, implying movement to the left.

Although the members of her retinue are not explicitly named in the mosaic, one might infer that Antonina is featured since she was a prominent female figure in the Byzantine world and a friend to Theodora. This inference can be made based on Antonina’s clothing and features alone. Theodora and Antonina share robes of similar hues – both are a dark brown with gold embellishments on the fabric’s edges, as well as accents of red and green within the details that mirror those on the vibrant red and green borders of the mosaic. Antonina’s head is covered with a headwrap that matches her intricate cream-colored shawl. At the edge of the shawl is a gold accent, which may be a brooch representing a crest. This brooch is also indicative of Antonina’s political standing as both the wife of famed general Belisarius and Theodora’s closest advisor and confidante. The only element of Antonina’s outfit that matches the remainder of Theodora’s court are her red shoes, just barely visible under several layers of woven cloth. The other female members of the court have similar facial structures and are viewed in profile. However, one can distinguish Antonina due to her unique features and frontal view.

Unlike the other members of the court, Theodora and Antonina look directly at the viewer, making eye contact with calm, collected stares. Their political relationship and friendship were integral to Byzantine society during this period, especially since Foss emphasizes Antonina’s significance in Theodora’s life, providing support during Theodora’s ongoing protection of persecuted Monophysites (Foss 2002, 146). As both Fisher and Procopius state, Antonina’s characterization somewhat mirrors that of Theodora; both were powerful women who exerted influence over their husbands to rise through political ranks.

Justinian

Justinian is flanked on both sides by members of the clergy, important generals, and military personnel with an emphasis on the figure dressed in gold vestments to his left. The figure is clearly the Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna, and his name is clearly marked above his head. Maximianus became the archbishop after 540 CE, following the long rule of the former Archbishop, Victor. Victor had been one of the patrons of San Vitale and had major influence over the creation of Justinian and Theodora’s mosaics. Justinian’s mosaic originally included Victor at his side, but his portrait was later removed and replaced with that of Maximianus following his death (Herrin 2020, 168). In his hands he holds a cross while Justinian gestures toward him with a golden bowl full of bread. A second priest holds an ornate book, likely the Bible, and a third holds burning incense. These objects are essential to the Orthodox liturgy, and specifically reference the blessing and distribution of the Eucharist. Justinian leads the procession, his head adorned with a halo, emphasizing his essential role as both a political and religious leader. Each member of the clergy, along with Justinian, face the viewer at a frontal position, and they seem to approach the onlooker with their holy procession.

The soldiers flanking Justinian on his right provide a striking foil to the religiosity of the scene. Each of the soldiers has a similar facial structure, mirroring the homogeneity of Theodora’s court, and they face Justinian, almost in profile to the viewer. It is likely that the figure directly to the right of Justinian is Belisarius, a powerful general, imperial advisor, and husband to Antonina. Although the figure between Belisarius and the soldiers is unnamed, one can infer that he is another important member of the military, perhaps a general himself due to the similarity in costume to Belisarius. The stark contrast between the religious and the imperial show two separate sides of Justinian – he was both the leader of an empire and an important figure in the church.

Cultural Significance

Theodora’s mosaic resides in the holiest part of San Vitale - in an apse flanking the altar, directly across from a matching mosaic of Emperor Justinian I. Scholars note that the placement and overall presence of the mosaics in San Vitale is unique. Byzantine rulers typically were not portrayed within churches, regardless of their patronage. While mosaics of Theodora and Justinian would have been common throughout the Byzantine world during their reign, a church seems like an odd choice of placement. Of course, mosaics would have been present in public and imperial spaces, serving as propaganda supporting the empress and emperor. However, Herrin notes that prior to the mosaics in San Vitale, images of royalty had no place in sacred settings (72). In fact, neither Theodora nor Justinian had ever visited Ravenna during their lifetimes, and would have never seen San Vitale in person. Why were their mosaics present in the Basilica if they had never even seen it?

According to Herrin, images of Arian Gothic rulers were prevalent in Ravenna and the Northern Italian region in the 6th century prior to Byzantine occupation and control. Once Byzantium had taken control of Ravenna, it became essential for Theodora and Justinian to assert their power and dominance since the capital of the empire, Constantinople, was far from the area. Ravenna was on the outskirts of the Byzantine empire, so it was imperative that the imperial family assert their influence over a potentially volatile population. Theodora and Justinian’s mosaics served to portray the power of Byzantium and the rule of the imperial family over the region, as well as emphasizing the new influence of Catholicism as the imperial religion.

Conclusion

Was Theodora the “harlot queen” or the “believing queen?” Without her own voice, it is impossible to create a fully accurate picture of her life. Procopius’s accounts of Byzantine history are some of the few recordings we have describing Theodora, and his blatant misogyny and insensitivity paint her as vindictive and vicious. However, we cannot discount Procopius entirely. Although it seems that his opinions on Theodora were fickle at best since his accounts of her character differ greatly between Historia Arcana and History of the Wars. His writings provide some background information about Theodora’s early life which can be interpreted through a feminist lens to counteract his cruel depictions of the empress. Theodora was both a “harlot queen” and “believing queen,” even if harlot is too derogatory a word for her. Various sources reveal that Theodora was likely a dancer and courtesan, but was also a deeply religious woman who protected a persecuted group. Even though her origins were quite humble, she eventually became the most powerful woman in Byzantium and practically an equal to the emperor. Regardless of her past, Theodora managed to rise through the ranks, becoming a close advisor and confidante to her husband, particularly in times of peril. This is clear through her rousing speech during the Nika Riots, her influence in the fight against Monophysite persecution, and laws she enacted that outlawed forced sex work and protected women working as performers. Her background complemented her position of power later in life; Theodora was an advocate for those living on the margins of society, assisting her husband in changing a constantly shifting Byzantine culture.

Bibliography

Brooks, Sarah. “The Byzantine State under Justinian I (Justinian the Great).” Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 2009. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/just/hd_just.htm.

Browning, Robert. “Hagia Sophia and the Reconquest of Africa.” Essay. In Justinian and Theodora, 73–100. London: Thames and Hudson, 1987.

“Empress Theodora with Her Retinue.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, n.d.

Evans, J A. S. “The ‘Nika’ Rebellion and the Empress Theodora.” Byzantion 54, no. 1 (1984): 380–82. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44170874.

Evans, James Allan. The Power Game in Byzantium: Antonina and the Empress Theodora. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011.

Fisher, Elizabeth A. “Theodora and Antonina in the Historia Arcana: History and/or Fiction?” Arethusa 11, no. 1 (1978): 53–79. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/26308163.

Foss, C. “The Empress Theodora.” Byzantion 72, no. 1 (2002): 141–76. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44172751.

Greatrex, Geoffrey. “The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal.” The Journal of Hellenic Studies 117 (1997): 60–86. Hagia Sophia: Istanbul’s Ancient Mystery. NOVA. Thirteen - New York Public Media, 2015. https://www.thirteen.org/programs/nova/nova-hagia-sophia-istanbuls-ancient-mystery-pro/.

Herrin, Judith. “San Vitale, the Epitome of Early Christendom.” Essay. In Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe, 160–73. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Howe, Eunice D. “Luke.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T052395.

Lymberopoulou, Angeliki. “Sight and the Byzantine Icon.” Body and Religion 2 (2018): 46–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1558/bar.36484.

Munroe, Nazanin Hedayatq. “Dress Styles in the Mosaics of San Vitale.” Metropolitan Museum of Art, June 25, 2012. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2012/byzantium-and-islam/blog/topical-essays/posts/san-vitale.

Murray, Charles. “Justinian I, Emperor of Byzantium.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T045386.

Nordhagen, P J. “Basilica of San Vitale .” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1093/oao/9781884446054.013.90000369944.